You had no choice but to read this article

You had no choice but to be right here, right now. In other words, you have no free will. Like none at all. “Why of course we have free will!” You say. Give this article a read. Let’s see if I can convince you otherwise!

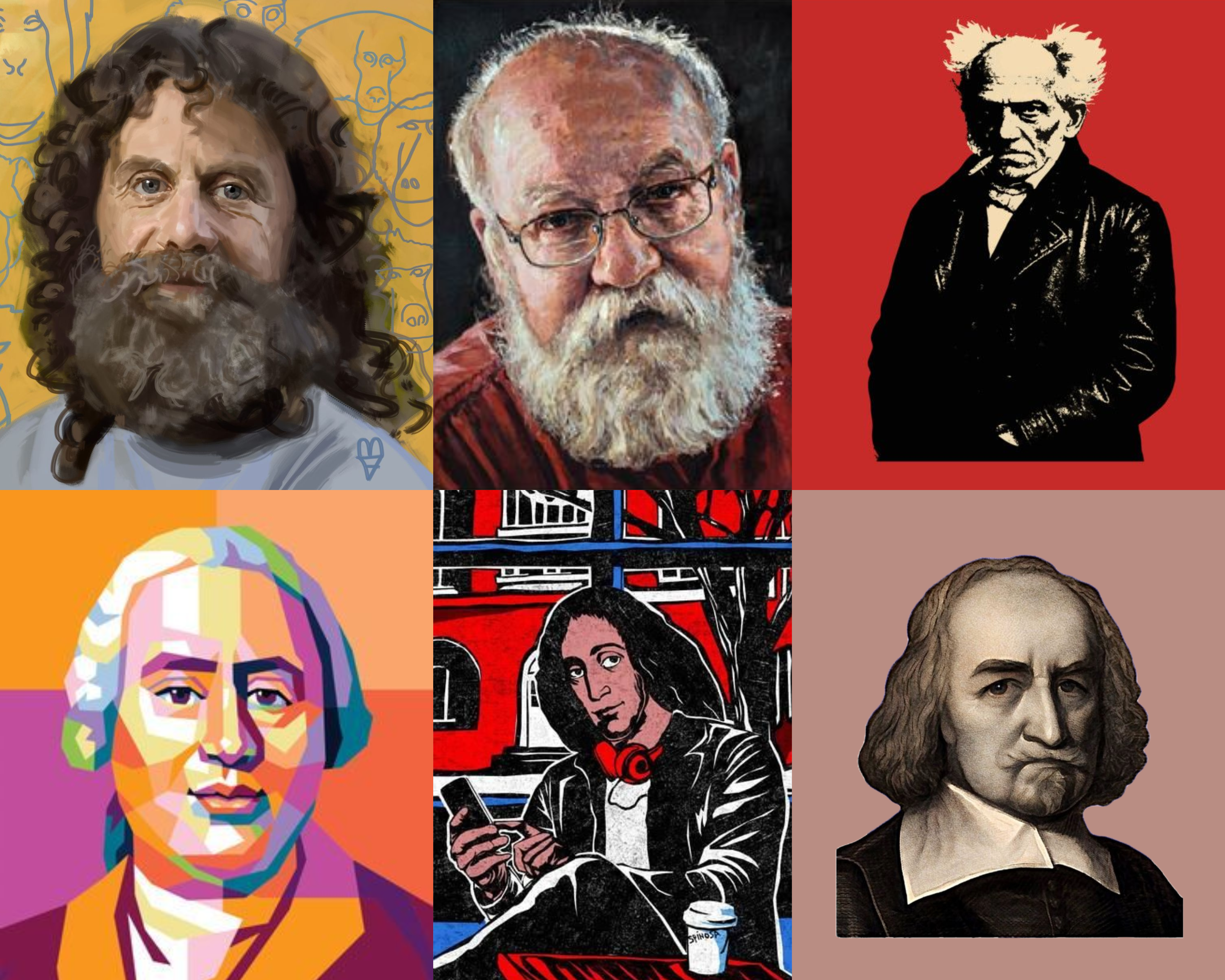

Are we really free? Ah, what a question! A question that Aristotle and Plato grappled with, that Hobbes and Hume wrestled with, that Dennett and Harris may have answered with modern science. Take a second to notice, however, that Jackson isn’t a name you see up there with the greats; it isn’t my hope, nor is it my expectation, that you will exit this article with an easy answer; I do hope, however, to expose you to provocative ideas that will encourage you to embark on some philosophical questioning yourself. As you read through, I urge you to try your hardest to prove me wrong, and then shoot me an email with your argument! Okay—onwards now.

When you saw the title of this article, you had a choice: read the article or not. At least, that’s what it seems. But what if I told you that you may be wrong? That you had no choice but to read this article? That every action you take isn’t free at all, but predetermined? You clicked on this article presumably because you were at least slightly interested in it. Perhaps you were drawn in by the title, or the fact that you’ve enjoyed my writing in the past and wish to see what I have to say. But you could’ve also easily not clicked on the article even if you were interested, right? Would our world be any different than it is today?

Say we rewinded all of spacetime so that we restarted our entire universe: the Big Bang, the single celled organisms, evolution, agricultural revolution, industrial revolution, etc. In that world, after returning to this very moment in time, would you still have chosen to click on this article? Or could you have chosen not to? Intuitively, the answer is, “Well don’t be silly! Of course I could’ve decided either way! I could’ve clicked on the article or chosen not to.” This is essentially what it means to have free will. But, for the sake of clarity, I’ll lay out a working definition that’s roughly kinda sorta borrowed from philosopher David Hume (I’ll elaborate on why it’s “roughly kinda sorta” later in the article):

There’s some decision we have to make. (For my purposes, whether to do busywork or not.)

If we chose to do one thing, but we could’ve chosen to do something else, then we have free will. (For my purposes, if I read Schopenhauer, but I could’ve chosen to do busywork, then I’d have free will.)

Undeniably, the illusion of free will is so immensely powerful that most of us would probably believe we had free will even if we could logically and scientifically prove that we didn’t. But that’s exactly what I’ll try to do using the following arguments. Before that, however, I should say that there are many different approaches that favor the deterministic view (that is, everything in the universe is predetermined and free will doesn’t exist), and I’ll go through each in the sections below.

The Philosophical and Logical Approach

In his essay On the Freedom of the Will, German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer asks free will libertarians (advocates of complete free will) a very simple question: Can you will what you will? Okay, woah—that may seem confusing at first, so let’s use an example that may help clear up what Schopenhauer means.

Suppose that you don’t like doing homework, so you decide that you’re not going to do the assignment. Schopenhauer’s point is this: could you have wanted not to want to do homework? In other words, could you have chosen whether you liked to do homework or not? A quick distinction: Schopenhauer is not asking, “Could you have chosen to act on your wants?” Basically, Schopenhauer, unlike some other philosophers and scientists we’ll talk about in a minute, is saying that while we can choose to act on our desires, those desires in the first place are not in our control; and, therefore, we don’t have free will.

And we can keep pushing his question as follows: Can you will what you willed to will? Or, using our homework example, could you have chosen to choose whether you like doing homework? Put differently, could I choose whether or not to choose to like doing busywork? By asking the question an infinite number of times, we commit a fallacy called an infinite regress, which just means that by requiring our belief to be justified by a prior cause continuously, we never reach the root original cause and therefore will never reach a real answer.

Now, I can’t choose to enjoy doing busywork no matter how hard I try; it’s something out of my control. Perhaps it's because of my biology (my brain gets bored of doing the same thing over and over) or my past experiences (doing busywork throughout middle school) or the current circumstances I’m dealing with at the time (maybe I had a back injury). Therefore, I have no free will when it comes to homework. And if you extrapolate this to every other action you take, you’ll find something—past circumstances, biology, your upbringing, the environment in which you live—that proves you didn’t have control over your decision! Just identify the want and ask yourself, why do you want this?

But if that purely philosophical approach doesn’t convince you, let’s talk about something that may: the thesis of casual determinism.

Remember when I said that if we were to rewind the universe back to the beginning and pressed play, everything would end up exactly the same way again? This idea of ultimate predetermination, conceived of by French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, goes something like this: imagine there’s a demon—a hypothetical super-intelligent entity (like artificial general intelligence) that knows the precise location and momentum of every atom in the universe at the beginning of creation. Laplace argued that if such a demon existed, it could use the laws of physics to calculate the entire future and past of the universe with perfect accuracy. Everything that would ever happen, every “decision” you would ever make, would be as predetermined as the orbit of the planets. That’s brutal. If Laplace is right, then we humans are nothing more than robots made of meat rather than metal. But it really feels like we’re more than just walking pieces of flesh, right? Is Laplace right?

This idea that the “future is entirely determined by the conjunction of the past and and the laws of nature” is known as causal determinism. But it isn’t the only way of looking at this free will debate.

Recall the beginning of the second paragraph of this article: "When you saw the title of this article, you had a choice: read the article or not." Okay…that statement is true, yes—but it's missing a layer of depth that could also indicate our lack of free will. What the sentence should've read is perhaps something like this: "When the rods and cones in your eyeballs detected photons bouncing off the pixels displaying this title, they converted that light into electrical signals that traveled through your optic nerve to your visual cortex, which processed the patterns and forwarded them to your language centers, which decoded the meaning and sent it to various brain regions that evaluated the content against your memories, interests, and current emotional state, ultimately producing a cascade of neural activity that resulted in your finger moving to click the link—you had a choice: read the article or not."

The word “choice” now seems almost comically out of place, doesn’t it? What happens in your brain when you think you’re making a decision is honestly pretty disturbing. In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet conducted an experiment that fundamentally changed our understanding of conscious choice. While they did this, Libet measured their brain activity using an EEG and asked them to note the exact moment they became aware of their decision to move by watching a clock. He found that the brain showed a spike in activity—what's called a "readiness potential"—about 350 milliseconds before the participants reported being consciously aware of their decision to move. In other words, your brain has already begun the process of initiating an action before "you" consciously decide to take that action. The subjective experience of making a choice appears to come after the brain has already committed to it.

Your consciousness, then, isn’t the reason for your actions; it’s more like an after effect that takes credit for decisions that some unconscious neural processes have already made. In 2008, researchers at the Max Planck Institute used fMRI scans to predict simple binary decisions (like whether someone would press a button with their left or right hand) up to seven to ten seconds before the person reported being aware of their choice. Seven whole seconds! Put differently, your neurons are already firing in a way that determines your “choice” long before your conscious mind has any idea of what you’re going to do.

Neuroscientist-philosopher Sam Harris takes this evidence and argues that if you pay close attention to your own experience—really pay attention—you'll notice that you don't actually author your thoughts at all. Try it right now: decide what your next thought will be before you think it. You can't. Thoughts simply appear in consciousness. You don't choose them; you witness them arising from...somewhere. That "somewhere" is your unconscious brain, which is grinding away according to the laws of cause and effect.

Harris writes: "You are not controlling the storm, and you are not lost in it. You are the storm." Your thoughts, your desires, your decisions—they all arise from prior causes. The firing of neurons, which itself was caused by prior firing, which was caused by your genes, your experiences, your neurochemistry, your environment, all the way back to factors you clearly had no control over. He essentially concludes that you don't choose your next thought any more than you choose when your heart will beat next.

And this idea extends to our preferences. Have you ever really thought about why you like the things that you like? Why do you find certain foods scrumptious and others repulsive? Why are you attracted to, say, blondes rather than brunettes? Why are you an introvert and not an extrovert?

These are all important questions because they’re what make you, you. And yet, it all comes down to biology, and you had no say in any of it. Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford professor of neuro-stuff, notes that at every layer of our tendencies—our immediate neurological activity, the hormonal state in the seconds to minutes before, the neuroplasticity caused by experiences over the previous months and years, the adolescent development of the brain, the genes you inherited, the culture you were born into—there are causes that we didn’t choose. You couldn’t choose your genes, or the parents you got. You couldn’t choose to be born as a human rather than as a lizard or, I don’t know, a rock.

Consider the fact that a tumor in the frontal cortex can turn a normal teacher into a pedophile, not because the person “chose” to become mentally ill, but because the tumor disrupted the delicate balance of neurochemicals that regulates impulse control and normal social behavior. When the tumor is removed, the person returns to normal. Does “free will” fit in that equation? Which version of the person is the “real” one making “free” choices?

Or what about Phineas Gage, a 19th century railroad worker who was almost killed after an iron rod blew through his frontal lobe. Before the accident, Gage was responsible, industrious, well-liked; after, he was impulsive, profane, and unreliable. He was “no longer Gage.” Did Gage have free will? Or was he just unlucky?

So, “you”—your personality, your values, even your choices—are dependent on the physical structure and chemical state of your brain: alter the brain and you alter the person. And, obviously, no one “builds” their own brain. We inherit our brains and it shapes according to our experiences and things we’re exposed to as we live our lives.

Moral Responsibility

Holy moly, we made it! But even if you’ve been convinced that you don’t have any free will—that free will is an illusion—what about moral responsibility? If what we do isn’t really our fault, but rather an inevitable result of an incalculable sum of our past, our neurochemistry, and our current circumstances, all of which are out of our control, then who is responsible for our actions? How can we justify punishing people for crimes they were neurologically destined to commit? How can we execute the Hitlers and Husseins of the world? This is where I find determinism to be extremely difficult to adopt. Intuitively, deep to my core, I believe those types of men deserve to be executed. This is also where the philosophy gets uncomfortable.

Hard determinists would argue that Hitler isn’t morally responsible in the way we typically think. He’s more like a dangerous natural phenomenon, like an earthquake or tornado, than an evil agent who “deserves” punishment. This doesn’t mean that we open the prison doors; we can still justify getting rid of the Hitlers of the world on the same grounds we’d justify quarantining someone with a COVID.

I personally find this ridiculous, even though it’s logically the “correct” answer. Thankfully, there is another option: a philosophy known as compatibilism. Not everyone is ready to accept such a profoundly strange gut reaction against that bleak picture. Many philosophers are compatibilists, who argue that free will and determinism can coexist; we’ve just been thinking about free will in the wrong way.

Daniel Dennett, the guy with the big bushy beard in the top-middle of this article’s featured image, argues that free will is indeed real when we have the ability to respond to reasons, to deliberate our options, and to act according to our own desires and values without external coercion. For Dennett, it doesn’t matter if your desires themselves were caused by factors outside your control; it matters that you’re acting on your desires or whether you’re being forced to act against them.

Consider the difference between these two scenarios: In the first, I carefully deliberate about whether to donate money to charity, weigh my reasons, consider my values, and ultimately decide to donate. In the second, someone puts a gun to my head and forces me to hand over my money. Compatibilists say there's a meaningful difference here, and that difference is what we mean by free will. In the first case, I'm free even if determinism is true. In the second, I'm not.

Going back to our homework example from earlier: even if my dislike of busywork was entirely determined by my biology and experiences, I still have free will when I choose not to do it based on that dislike. I'm acting on my own will, my own reasons. The fact that my will was shaped by prior causes doesn't make it any less mine.

By being a compatibilist, we can also retain our idea of moral responsibility. We can still execute the Hitlers and Husseins of the world because they acted according to their own rational deliberation. Deliberating and acting impulsively are two different things, and when faced with the choice between either, we do indeed have free will. In this way, we can hold people responsible through punishment and therefore change the causal chain that influences future behavior.

Why does this even matter?

If all the arguments point toward the non-existence of free will, if neuroscience shows our conscious decisions are just post-hoc rationalizations of unconscious neural events, if the logic of ultimate responsibility leads to an impossible regress, then what in the universe (literally) are we supposed to do with this information?

Free will is strange: even if you become intellectually convinced that free will doesn’t exist, you can’t escape the subjective experience of choosing. Right now, as you read this, you feel like you're deciding whether to keep reading or stop. Tomorrow, you'll feel like you're choosing what to eat for breakfast. You'll deliberate, weigh options, make plans, all while experiencing the unmistakable sensation of being an agent who could do otherwise.

Perhaps this is how it has to be. Maybe the subjective experience of free will is so fundamental to human consciousness, so essential to how we navigate the world, that evolution built it too deep into our brains to remove. We're condemned to be free, as Sartre might say, or at least condemned to feel free, even if we're not.

What's clear, however, is that you didn't choose to finish this article. The causal chain that began with the Big Bang, that ran through billions of years of cosmic and biological evolution, that shaped your particular brain with its particular interests and attention span, that placed you in front of this screen at this moment—all of that determined that you would read to the end.

And now, in your brain, neurons are firing in response to these words. Chemical signals are rushing through synapses. Unconscious processes are generating thoughts and feelings that will soon bubble up into your consciousness as "your" reactions, "your" beliefs about free will, "your" decisions about what to do next. You are a universe experiencing itself, a small eddy in the great causal river, a pattern of matter and energy briefly aware of its own existence before dissipating back into the void. Whether you call that free will or determinism almost doesn't matter. What does matter is that you're here, reading this, thinking about it. And that's already extraordinary enough, chosen or not.